Beyond Modern Nihilism: The Revival of Symbolism and Beauty in Art

Art, in Indian philosophy, is made to stimulate rasa. It’s Sanskrit for “essence, flavour, or taste”—an essential part, if not the most important, for any work of art.

In your light I learn how to love. In your beauty, how to make poems. You dance inside my chest where no-one sees you, but sometimes I do, and that sight becomes this art.

- Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi

Art, in Indian philosophy, is made to stimulate rasa. It’s Sanskrit for “essence, flavour, or taste”—an essential part, if not the most important, for any work of art.

Rasa is a transcendental aesthetic experience; experienced, but not easily described. It’s the highest form of encounter art. This concept is related to experiencing spiritual bliss—a mystical moment of becoming one with the infinite. Similar to beauty as a transcendental. Transcendentals are properties all things share by virtue of their existence.

Rasa only manifests when three things are present in a work of art: Object-Subject-Union.1 This trinitarian formulation is how an artwork becomes timeless.

The Object: Art and Artist

Firstly, rasa hinges on the artwork itself. This is the object. Object is twofold: art and artist; starting with the art. The art must be beautiful whether it’s performing, literary, or visual art. And the art must always point beyond itself towards the infinite whether it’s visually capturing the form of Kali through sculptures or portraying the divine love between Krishna and Radha in a painting (see Fig. 1).

Take Fig. 1. You see in visual form the nuptial union of Krishna and Radha. Krishna is the avatar of Vishnu, the Supreme Reality (see my post on the Bhagavad Gita, especially the footnotes). Radha is his consort. When both Krishna and Radha are depicted in paintings or sculptures Radha represents bhakti, or devotional worship, to Krishna. In light of this, Radha is a stand-in for your devotion to Krishna. Hence this watercolour piece portrays a form of nuptial mysticism—where you, as Radha, are united with the Ultimate Reality, Krishna.

All this requires knowledge of the symbolism at play. And through this understanding, the viewer’s consciousness is raised. So the art itself then becomes a medium of initiation; bringing the viewer into a tradition. A tradition filled with history, life, meaning, culture, and faith.

Within the painting in Fig. 1. there is much symbolism at play, from Krishna’s lotus crown to the lotus bed to the use of colours. But that’s for another time.

Now contrast this with some Modern and Contemporary art.

Take, for instance, artworks created by dripping paint onto horizontal surfaces. Even if one of these contemporary pieces sells for $140 million (see Fig. 2, which did sell for that price), at best it is inferior to Fig. 1, and at worst it’s not even art. Not only is there a lack of artistry involved in the creation, but the art itself is simply nihilistic insofar as it doesn’t attempt to capture a deeper meaning by going beyond the surface to revive a world of symbolism, harmony, and beauty.2

In Pollock’s No. 5, what you see is exactly what you get—its meaning is entirely exoteric. This characteristic is prevalent in much of modern and contemporary art. You might argue, “There is a hidden meaning in Pollock’s art—it lies in how it makes you feel. Art is about this subjective experience and personal interpretation.” But this is precisely the problem. Viewing art solely through the lens of personal sentiment reduces it to mere subjectivity. It assumes that art has no intrinsic value beyond our own instrumental use, whether for political or personal ends.

As a result, these artworks fail to initiate viewers into a deeper understanding. They do not transport us to subtler realms of history, life, meaning, culture, or faith.

Intrinsically connected to the art, then, is the artist—the second part of object. The artist’s ability and skill to capture concepts, and accurately portray stories or allegories through lines, symmetry, colours, composition, style, etc is paramount. Underlying all this is creativity. The artist must be creative, filled with wonder and not hopeless.

Because of this, the artist is obligated not only to practice his craft consistently but hone his mind through study and contemplation.

The artwork, if it’s visual like a painting, doesn’t have to be hyperrealistic nor must it have dimensionality. Clearly Fig. 1 is flat. The dimensions are all off. And there’s no visual depth. Compare this to William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s paintings (see Fig. 3.).

Bouguereau's ability to capture in great detail the human body — the softness of skin, and the warmth of holding your lover in your arm is second to none,3 and why his work was always exhibited at the Paris Salon. He focused his energy on painting mythological themes. You see in many of Bouguereau’s painting the two-fold nature of object: (i) artwork illustrating themes of transcendence and (ii) his artistic mind and skills.

Interestingly, Bouguereau’s painting fell out of fashion until the 1970s. And he confessed much of his later works were driven by market demands,

“What do you expect, you have to follow public taste, and the public only buys what it likes. That's why, with time, I changed my way of painting.”4

His art at this point became superficial. And superficiality is where artists’ souls go to die because you begin creating not out of wonder but to appease buyers.

As Aristotle says,

“For it is owing to their wonder that men both now begin and at first began to philosophize.”5

Without wonder are we any different than beasts?

For great artwork expresses what words cannot. Ideas which are much too subtle, mysterious, and paradoxical for language. Such that they can only be encountered through artwork.

Bouguereau’s a good example, despite the superficiality of his later works, to show that the problem is with the public—the Subject. It’s as if the public suffers from dysgeusia, a disorder that distorts your sense of taste. Often people with dysgeusia say food, no matter the flavour, tastes metallic, bitter or rotten.

In our situation, it’s rasa dysgeusia: the inability to decipher beauty from ugliness. This is where the second part of the trinity, subject comes into play.

The Subject: The Viewer’s Role

Crucial for experiencing rasa is you, the viewer, the Subject. It’s in this union of object and subject that rasa is aroused, hence the trinitarian Object-Subject-Union. Without the subject, the object is dormant. Waiting to be awoken.

However, there’s a massive qualifier within subject. What is that which rasa cannot occur, no matter how intentional the artwork is? That, my friend, is knowledge. Without knowledge, an object can come into contact with a subject and nothing takes place—no rasa is ever evoked. Put differently, an artwork imbued with “flavour”, “essence”, or beauty can be observed by a viewer, and the viewer can leave unaffected and unnourished.

The reason for this is that the viewer, in this case, is not a raiska (intuitive experiencer) and a rasajna (analytic knower). A raiska is one whose taste is refined and can appreciate “flavour”. And rasajna is one who has attained knowledge/truths such that they can discern beauty.

And only when you have cultivated your taste and knowledge to discern beauty from ugliness, and to see what the symbolism points toward, can you experience and participate in rasa. This means there’s a calling upon you to hone your taste and knowledge. And this is done through contemplation and study.

If you’re not honing your senses and mind, then viewing, owning, and creating art are simply nonsensical endeavours. It would be like giving a child a pearl necklace or asking a child to write poetry before they can even speak full sentences. The child, unless they grow and mature, will never appreciate what’s in their possession nor will they write poetry.

The Union: Bringing Art to Life

Only in this proper unification of object and subject does the trinitarian Object-Subject-Union come alive.6 And it is here that art marries the finite with the infinite, allowing the viewer to experience eternity in a single glance. This then becomes good art. Nay, timeless art.

Jacques Maritian writes in Art and Scholasticism:

The Fine Arts aim at producing, by the object they make, joy or delight in the mind through the intuition of the senses: the object of painting, said Poussin, is delight. Such joy is not the joy of the simple act of knowing, the joy of possessing knowledge, of having truth. It is a joy overflowing from such an act, when the object upon which it is brought to bear is well proportioned to the mind.7

Here he is declaring that when the object (art) and the subject (viewer) are aligned there is a higher type of joy which proceeds from the unification of possessing knowledge and tasting the essence of the art.

In light of this understanding that good art is trinitarian, we begin to understand the distinction between good and bad art, between beauty and ugliness (See my short essay on how disconnecting ourselves from architectural beauty has led to dire social consequences here).

From this perspective, many contemporary art, artists, and collectors are like children who think mud pies are no different from pumpkin pies. Either they’re deluded into believing that the large painting hanging in their foyer of rectangular colours is a timeless, beautiful masterpiece, or they are the artist who painted this work. In both instances, raiska and rasajna are missing. And consequently, no rasa.

Art then is intrinsically human. Indeed it’s the most human thing we could do and experience. It ties our rational and intellectual faculties to our aesthetic sense.

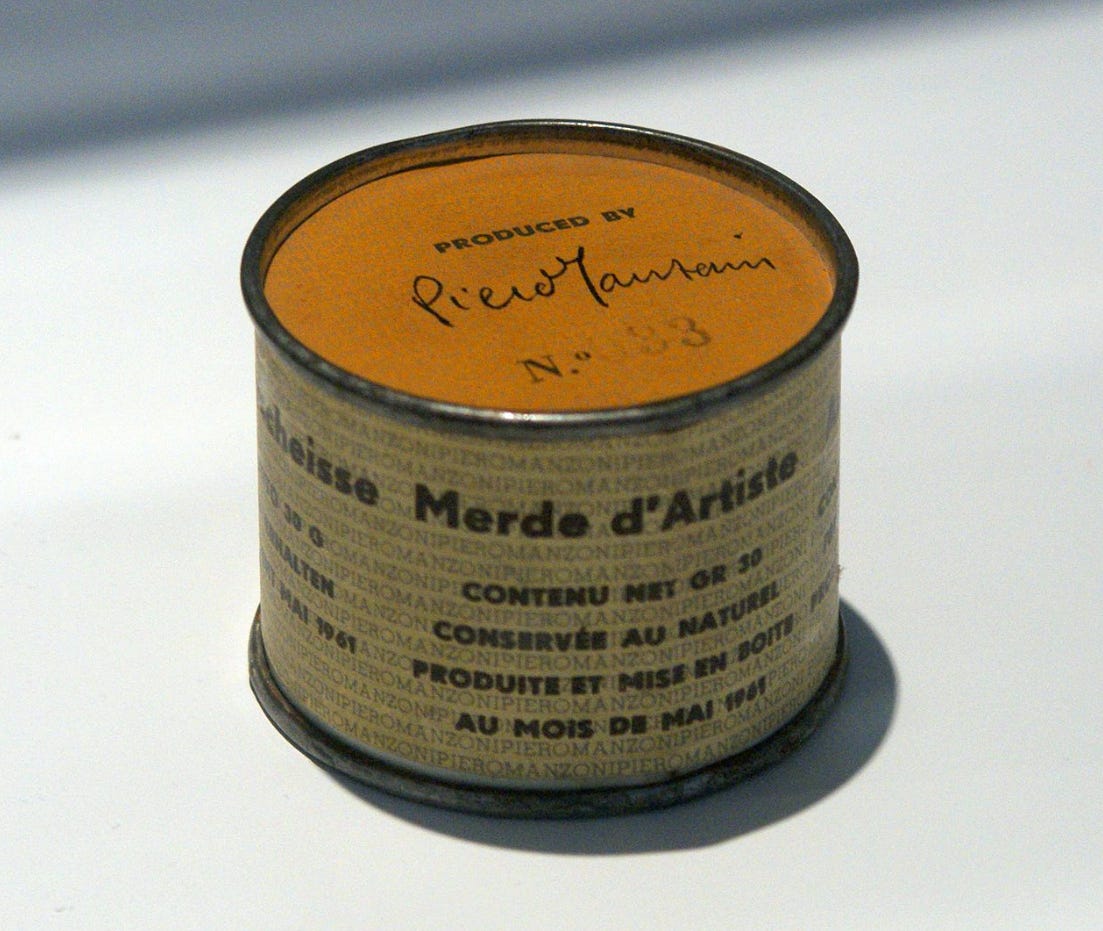

Modern Art: A Can of Shit

But sadly many collectors aren’t interested in nourishing their minds and senses to become raiska and rasajna. They’re comfortable collecting nonsensical pieces to impress other uneducated minds and underdeveloped tastes. This is partly due to ignorance; a fault born of ignorance is easier to remedy than one born out of desire. Nonetheless, many collectors are easy prey for media and marketing stunts. Otherwise, why would one purchase something like Untitled (America #3) (Fig. 4.), a work consisting of 12 light strings each with 42 bulbs, for $13 million?

On the flip side, many contemporary artists create because they want to “express” themselves or because they want to shock the world. Think Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (Fig. 5.) or Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (Fig. 6.).

Duchamp in an interview with BBC’s Joan Bakewell in 1968 asserted that his goal was to “discredit art”, and to “get rid of art” like we did “away with religion.” Following in Duchamp’s footsteps, Hirst placed a dead shark in formalin. When asked about the meaning of it… he didn’t know what it was supposed to mean.

Robert Hughes, an art critic, called The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living a “pretty meaningless object”. Going on to state,

“It’s a comedy but it’s a kind of tacky comedy too that bears a lot upon the way we think about art and how it is made.”

Art went from having “flavour” to flavourless. And we moderns are none the wiser largely due to our rasa dysgeusia. Our rasa dysgeusia is perpetuated by artists who treat their viewers as unintelligent apes whose minds can only be aroused by shock and disgust.

The goals for Duchamp, Hirst, and many others are far from arousing rasa. These artists don’t upload your human dignity, your intelligence, your innate longing for beauty. Rather they’d laugh at the concept of creating art to help finite viewers peer into the infinite, into the beautiful. It’s all mumbo jumbo. Modern art is about inciting shock and disgust! The more disturbing the art, the more coverage. The more coverage, the more desirable. The more desirable, the higher the price tag. So they justify their superficiality, much like Bouguereau did, for more dollars.

The truth is their art comes from a place of despair, of realizing (falsely) that nothing they do matters, that all of this existence is pointless. Their art is their attempt to create meaning through their will—their “will-to-meaning” to borrow Viktor Frankl’s terminology (for more on this listen to my episode on Frankl). But in this case, their will is futile in creating meaning because their art removes the central part of meaning, namely, connecting the finite to the infinite.

Art then is intrinsically human. Indeed it’s the most human thing we could do and experience. It ties our rational and intellectual faculties to our aesthetic sense.

But, today, art is nothing more than titillating our uninhibited animalistic desires. What is meant to be the culmination of our intellect and senses, is now literally a can of shit (See Fig. 7). Where do we go from here?

Reviving Rasa

Modern art fails because it fails to mean anything. It fails to mean anything because many modern artists are nihilistic. How can one create a meaningful masterpiece if the artist’s starting point is, “All is meaningless and pointless”?

Roger Scruton in his book Beauty writes:

“Art moves us because it is beautiful, and it is beautiful in part because it means something. It can be meaningful without being beautiful; but to be beautiful it must be meaningful.”8

You need artists who create art to arouse rasa, who are committed to cultivating their minds through wisdom to become raiska and rasajna themselves.

Isn’t Nihilism a good thing?

Hold on, you might say. Isn’t Nihilism precisely the mechanism that provides the artist with a blank canvas upon which the artist can be free to do as he or she pleases? So shouldn’t we celebrate the “death of art” as Duchamp wanted because now the artist is unshackled—free from the tyranny of constraints?

This presupposes that freedom is doing whatever one pleases. But is the truest form of freedom expressed best without constraints? For example, if you step into a dojo with no martial arts training and are matched up against a person with five years of training, who do you suppose will win? It’s unlikely it will be you—even if you were permitted to move your body any way you like. Instead, your opponent who has trained his body to move rhythmically and technically will defeat you. So, nihilism is like the man stepping onto the mats thinking that having no combative training unlocks true freedom to be competent at fighting. This is not freedom but ignorance. It’s the best way to destroy yourself. Unable to actually move in any meaningful manner, all his actions amount to wasted energy. So similarly true freedom is found within constraints, not lack thereof.

The Collector and Artist as Raiska and Rasajna

This is why the second part of the trinitarian formulation is crucial.

The subject within our trinitarian component of Object-Subject-Union is most neglected in our day. The reason is that (i) we’ve misunderstood freedom and (ii) we live in a nihilistic world where nothing “matters”. In combination, we’re unable to decipher truth from falsehood, beauty from ugliness, and wisdom from folly. Everything is meaningless and subjective.

Yet art at its highest, when rasa is awakened, is analogous to wisdom. In that we seek wisdom for itself, not as a means to an end. For wisdom is universal, not subjective.

Through wisdom, we learn to live lives filled with meaning. Jacques Maritian best expresses this:

There is a curious analogy between the fine arts and wisdom. Like wisdom, they are ordered to an object which transcends man and which is of value in itself, and whose amplitude is limitless, for beauty, like being, is infinite. They are disinterested, desired for themselves, truly noble because their work taken in itself is not made in order that one may use it as a means.9

Wisdom initiates the seeker by revealing complex, subtle, and even paradoxical ideas which are beyond mere expressions of words. Similar to how Tao is explained by Lao Tzu:

“Tao is beyond words and beyond understanding. Words may be used to speak of it, but they cannot contain it.”10

Art seen in this light is an end in itself. You stop collecting art to impress friends, other collectors, and museums. Instead, like wisdom, you seek beautiful art because it calls you to live the true human experience. And your art collection begins to mirror the harmonious union of object-subject: bliss.

This means not succumbing to the pressures of buying artwork simply because the prevailing opinion is that it’s a must-have. So dishing out $50k, $100k, $1m, or even $10m for a piece that doesn’t stimulate your mind or soul but satisfies your ego, only to be filled with buyer’s remorse, is no way to be a refined collector.

Whether you’re an experienced or an amateur art collector, your calling is to take seriously what you collect. You learn not only about art history but also about philosophy, theology and religion. Because, whether you’re religious or not, or think theology is pointless, or think philosophy is boring, great works of art that have stood the test of time are made by artists who have impregnated their metaphysics in their art. Not shallow, new-age ideas like self-expression or the meaningless pouring of paint onto the canvas.

Until very recently, many of the great artworks were inspired by ideas like imago dei (Christian concept of being made in the image of God), moksha (Hindu idea of liberation from reincarnation), itlak (Sufi path of Annihilation), chöd (Tibetan Buddhist practice of killing the ego), and the list goes on. The art was nourished philosophically, theologically, and psychologically by the artist’s commitment to honing his raiska and rasajna

Not only that. The collectors were immersed in these discussions even if they didn’t always agree with the subject. And often the collectors were patrons of the arts. In the East, think of Akbar the Great, a Muslim ruler, one of the most powerful Mughal emperors, whose sponsorship of court painting had an immense impact on devotional Hindu art, inspiring Rajut (Hindu) rulers to sponsor local artists to create court paintings retelling the stories of Vishnu, Krishna, Shiva, etc. Fig. 1, for example, is from one of the Rajput courts. In the West, think of the Medici family. Arguably one of the most influential families in art history (and beyond). Their patronage of artists brought Renaissance art to new heights.

So, the more you as the collector understand philosophy, theology, and religions, the more your intellect and your collection begin to transcend this contemporary nihilistic psyche. Through this, you start to taste the nuances of philosophy interweaving with theology and psychology in art. You can sense the topological (teaching a moral lesson), allegorical (seeing yourself in the art), and anagogical (experiencing a mystical understanding) meanings which are embedded within the work (I discuss this in my essay on interpreting the Bhagavad Gita). You witness the birth of the artist’s ideas as you stand before their works.

Your life as the collector is enriched through a deeper understanding as you experience the essence of the art. Further still, like the Medicis and Akhbar, your collection becomes timeless, impacting generations to come.

This call is equally, if not more, important for artists. The artists are both subject and object. Yet, because our artists exist within our nihilistic age, they often create meaningless art. Art that’s simply an expression of themselves. Or wholly self-absorbed. Or art that shocks the world. So bold and brave…

But it doesn’t have to be like this. The artist can wake up tomorrow and abandon his nihilism as Leo Tolstoy did (for more on this listen to my episode on him), and take seriously his calling to guide viewers into experiencing the ineffable. Or to transmit ideas that transcend words. And right here is where the trinity of Object-Subject-Union is enlivened.

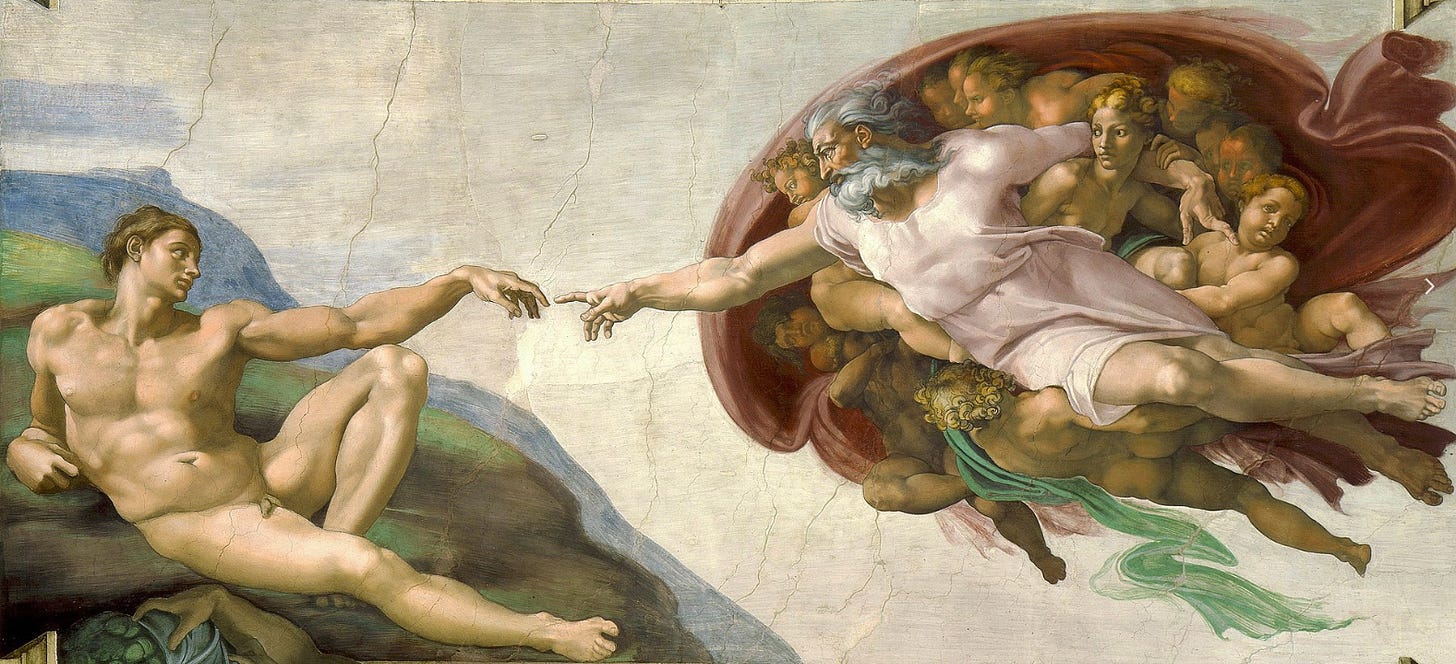

Hence, the intention of the artist is vital. Let’s suppose we give a monkey unlimited brushes and paint and an infinite amount of time. We’ll call this thought experiment, Infinite Monkey Artist.11 Could this monkey produce Pollock’s No. 5 (Fig. 2)? Yes.

But could this monkey produce The Creation of Adam (Fig. 8)? No. This is because Pollock’s No. 5 and many of his other works are the result of spastic movements. You could say his action painting was a dance, not random. Even still, there’s no meaning beyond the surface. In contrast, Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam is born from philosophical and theological knowledge, skills, and intention, designed to stimulate rasa.

A New Beginning

This is why, after a decade away from painting, I pick up my brushes with a purpose. I spent the previous decade studying philosophy, theology, religion, and science. But I too, like Maritian, realized that there’s a “curious analogy between the fine arts and wisdom,” and that arts are “ordered to an object which transcends man and which is of value in itself, and whose amplitude is limitless, for beauty, like being, is infinite.”

I want to create art that holds a deeper meaning. Art which goes beyond the surface to revive a world of symbolism, harmony, and beauty. Art that outlives me. Art that my great-grandchildren can view and be transported to a realm beyond. To revive rasa.

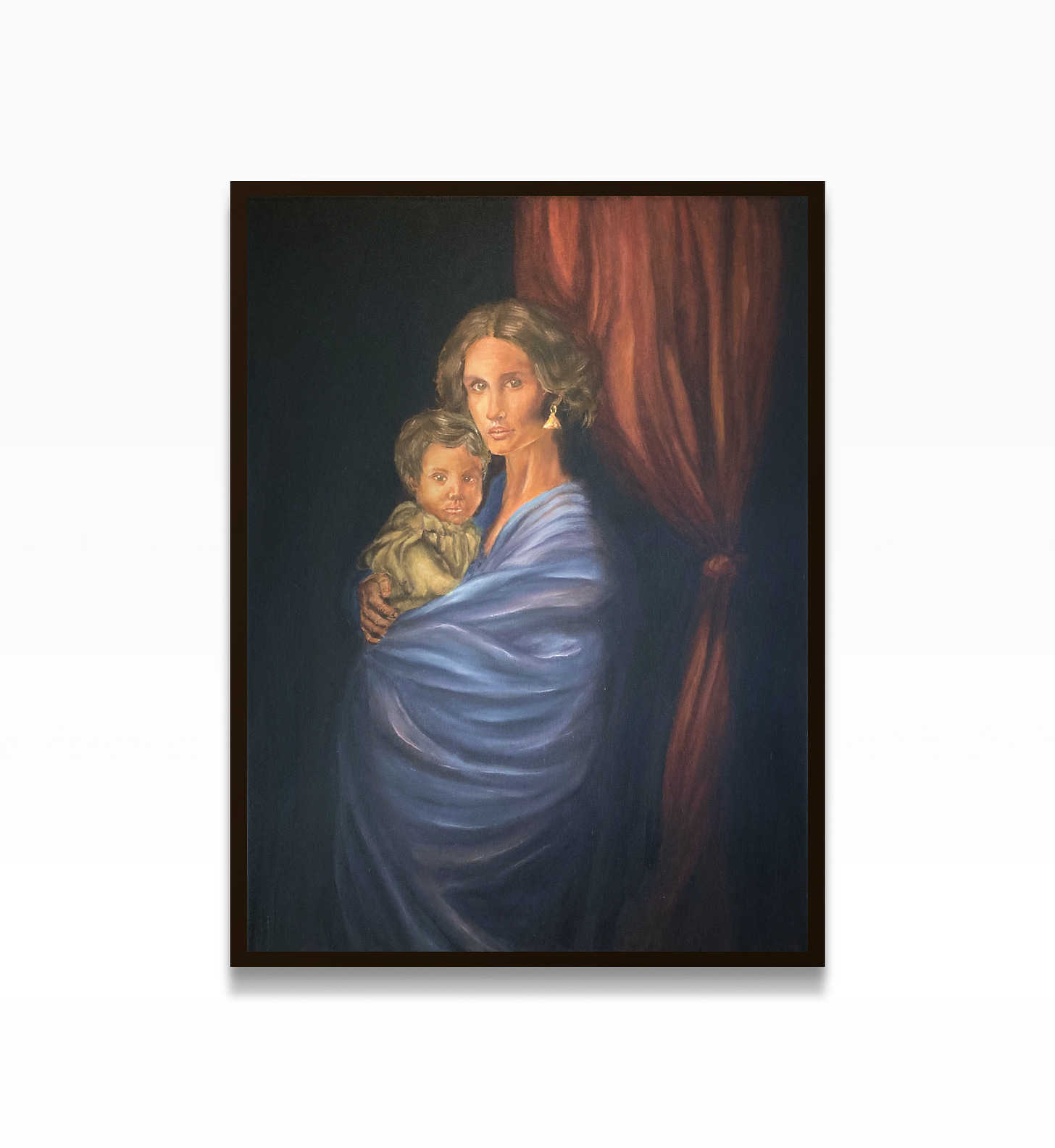

In that mission, my painting, ‘Mother and Child’ marks the first step toward that ideal.

‘Mother and Child’ portrays three realities.

Up front, we witness the story of humanity, a nurturing mother and her child.

In the second reality, the mother represents a nation, and the child is her citizen. The red curtains serve as a haunting reminder of the sacrifices during the nation’s birth, while the blue shawl draped over them conveys a sense of solemnity. It acts as a shield, protecting the vulnerable child while offering a glimpse into the past. The mother's scarred and aged hands show the hard work leaders endure to build a lasting nation.

The third reality explores the duality of human nature. First, the colours: red symbolizes the material world, strength, and expression, while blue represents the immaterial world, wisdom, and introspection—forming the human psyche. The mother symbolizes the creative force and the source of all life. Without her, there is no birth and preservation. The mother wears a triadic gold earring calling the viewer to listen and seek wisdom. The child wearing green symbolizes new beginnings and your journey toward attaining wisdom.

I’m not just critiquing modern art and lamenting the lack of beauty—that’s easy to do. I’m taking action to reveal a timeless truth about great art by creating it. I believe beauty is universal and that beautiful art can elevate individual consciousness to the transcendent.

I’m not merely suggesting that you, as a collector or artist, should invest your time studying philosophy, theology, and religion. I’m dedicating my time too; studying the wisdom of history’s greatest minds and creating weekly 40-minute episodes so that you can join me on this journey. The books I study inform and influence my paintings.

You’re here reading this because you also believe that cultivating your mind and soul to experience beauty is essential to being human.

My mission is to revive beauty and wisdom in the world through my paintings, my podcast, and these long-form essays. If my writing, podcast episodes, and paintings make you think deeper, inspire you, and you want to support my work and keep me creating, consider becoming a patron.

You can support this project by leaving a like, upgrading to a paid subscription on Substack, or joining my Patreon community.

Thank you to all those who have supported my work.

If you’re an artist, join me on this mission. If you’re a collector, join me by collecting beautiful art.

~

Till next week,

Peace.

*** Sincere gratitude to my early readers: Kaelynne, Amos, Mike, and Hugh for their feedback and insights. Your thoughtful comments and suggestions have significantly improved this work. Any remaining mistakes are solely my own.

I’m borrowing from William Stoddart’s here. Stoddart in “Mysticism” says Sat-Chit-Ânanda, which is usually translated as Being-Consciousness-Bliss, is formulaic of Object-Subject-Union. According to him, this trinitarian formula is found in all major religions. However, I’m using this formulation differently than him. My usage is to help expound on the mechanism behind rasa. Stoddart, William. "Mysticism." Sacred Web, vol. 2. 1998.

Now inherent within this understanding of object, the price tags have no impact in invoking rasa. For instance, if you bought actual crap for $1 million, the price tag doesn’t magically transform the essence of crap into gold. So similar just because you own an expensive piece of art, it doesn’t mean that this particular art (i) captures beauty or goodness, (ii) that it’s nearer to arousing rasa in any viewer simply by virtue of its price. This could be because the art is missing “flavor” or “taste” to begin with. Unfortunately, Piero Manzoni’s did create a piece called Artist’s Shit which is 90 tin cans, each with 30g of crap (See Fig. 4).

Bouguereau was considered one of the greatest painters of his time. However, Bouguereau's critics saw him as outdated because of his traditional academic style, and because he started painting simply to fill market demands. The critics saw this as an artist abandoning the spirit of creativity and freedom.

Jensen, Robert. Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-siècle Europe. Princeton University Press, 1996.

Aristotle. Metaphysics. Translated by W. D. Ross. Public Domain.

This trinitarian formulation applies to all forms of craftsmanship too. There’s a real sense that the Bladesmith, carpenter, and mechanic are all participating in art. Hence, a beautiful Katana or a Breitling watch can conjure awe in the viewer. The main difference is that the goal for craftsmanship is practical and the artist is “impractical” by nature of the subject. And so the craftsman’s work is to be “used” and has the accidental property of arousing rasa. Whereas, the nature of fine arts is the transmission of thoughts beyond words. And only accessible when the trinity is present.

Maritain, Jacques. Art and Scholasticism. 2nd ed. Cluny Media LLC, 2020. (First published 1933)

Scruton, Roger. Beauty: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Maritain. Art and Scholasticism. 52.

Tzu, Lao. The Tao Te Ching of Lao Tzu. Translated by Brian Browne Walker. St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

I’m modifying the famous Infinite Monkey Theorem. The idea that a monkey with an infinite amount of time and a typewriter, will likely type out the complete works of William Shakespeare. This is because the monkey will eventually hit all the possible combinations of characters.

Keep on painting. It's a beautiful visual representation of your philosophy.